© Mystic Seaport. Used with permission, 2015.

C.H. Fellowes

A 48 Year Old Tattoo Mystery Solved

Researched & Written by Carmen Forquer Nyssen

In 1966, an antique dealer in Providence, Rhode Island stumbled on the hand tattooing kit and design book of an obscure tattooer named C.H. Fellowes. These artifacts ended up with Folk Art Collector Barbara Johnson, and eventually, in the archives of the Mystic Seaport Museum in Mystic, Connecticut. Because of their rarity, the relics created quite a buzz in the tattoo world, particularly the design book.

In 1971, Pyne Press released the design book images in a publication entitled The Tattoo Book for which William C. Sturtevant, a Smithsonian curator, supplied insightful historical analysis and commentary.

Dr. Sturtevant had devoted countless hours trying to identify Fellowes. In researching, he consulted numerous New England area directories and newspapers and interviewed a good number of veteran tattoo artists. Frustratingly, his attempts failed to turn up any leads.

Yet, not all his efforts were in vain. Dr. Sturtevant was a staunch advocate of preserving history through “material culture.” He placed great importance on retaining artifacts so they could be studied in context of a given culture. His respective scholarly treatment of Fellowes’ design book ensured its curatorial and archival value, and therefore, its accessibility for further examination.

C.H. Fellowes A Boston Tattoo Artist

That’s where my research comes in. While studying the Mystic Seaport Museum’s digitized version of the design book, and my personal copy of the Tattoo Book, I discovered that the design book had held the key to the Fellowes’ mystery all along—albeit with an unusual twist.

© Mystic Seaport. Used with permission, 2015.

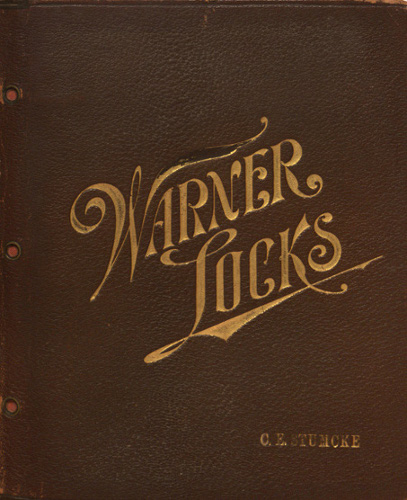

Though inscriptions and Victorian motifs within the book identify Fellowes as a turn of the century artist, they otherwise hint at little else up front. But the gold embossed lettering on the cover—“Warner Locks-C.E. Stumcke” —raises several questions: Who or what was Warner Locks? Who was C.E. Stumcke? And could these names be connected to Fellowes?

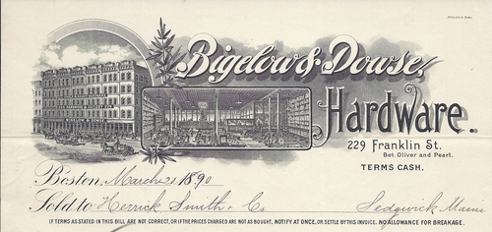

The answer to the last question is a resounding “Yes.” Through a little creative sleuthing in genealogical records and newspaper archives, I pieced together that Charles E. Stumcke, a long time Boston resident, was head clerk at the Bigelow and Dowse Hardware Company, one of the largest of its kind in New England. Part of his duties would have entailed buying inventory for resale. Judging by the lettering on the sketch book, he apparently made purchases from the successful Chicago based hardware company, Warner Locks.

To further the case, my research also uncovered a local man by the name of Charles H. Fellowes (aka Fellows). He was born February 27, 1869 in Killucan, Westmeath, Ireland to John Fellowes and Eliza Robinson; the family immigrated to the United States in the 1870s and made Boston their permanent home. By the time Fellowes was in his twenties in the 1890s, he was working in the hardware business as a shipping and packing clerk. Starting in 1897, the directory gives his work address as “229 Franklin.” This, as it happens, was the location of the Bigelow and Dowse Hardware Company, Charles E. Stumcke’s workplace.

Collection of Carmen Nyssen

1897-1898 Boston City Directory:

Charles E. Stumcke, clerk, 229 Franklin, house 542 Park, Dorchester

Charles H. Fellows, porter, 229 Franklin, boards 313 West Third

Tattoo Designs Tell a Tale

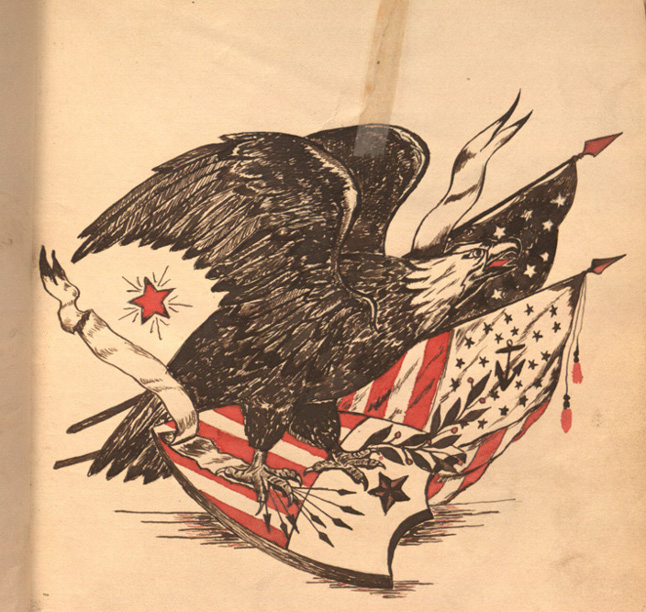

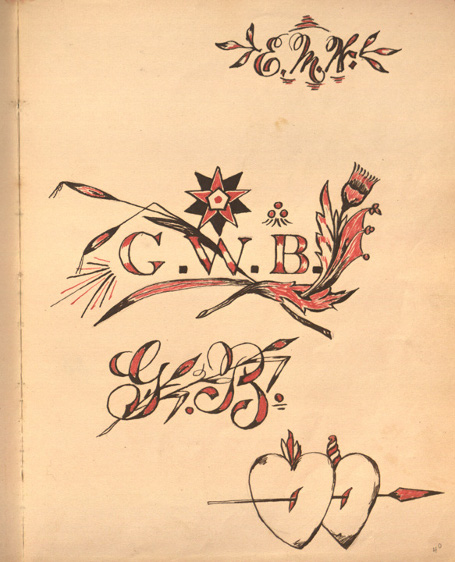

Although finding the connection between Stumcke and Fellowes was a step in the right direction, the biggest clue, the clincher, was yet to come. Fellowes’ design book offers an assortment of typical tattoo motifs. In addition to patriotic themes, the pages depict religious and mythological designs, and most importantly, the ever popular sweetheart initials. Lucky for us, Fellowes added a few personal touches to his drawings.

Several emblems include the monograms “G.B.” or “G.W.B.” Imagine my excitement, when I turned up a Boston marriage record for Charles H. Fellowes and “Jennie W. Baker.” Jennie was apparently a nickname for Genevieve or a similar name. The two were married January 10, 1895. Sadly, Jennie died the same year.

© Mystic Seaport. Used with permission, 2015.

Additional emblems incorporating the initials “C.A.S” or “C.A.F.” left no doubt that I’d found the correct man. According to Boston marriage records, the same Charles H. Fellowes married “Clara A. Steele” on June 29, 1898. She also died shortly after they married, in 1905.

© Mystic Seaport. Used with permission, 2015.

© Mystic Seaport. Used with permission, 2015.

Boston Tattoo History

Solving the mystery of such an elusive tattooer as C.H. Fellowes was a thrill to say the least. However, while identifying him was a major breakthrough, there are many unknowns awaiting discovery. Designs, such as battleship scenes from the Spanish American War, indicate that Fellowes had started tattooing by at least 1897-1898. Since one design is dated November 8, 1900, we know he was still tattooing then. But where did he work? Did he operate a tattoo shop? And for how long?

Perhaps he was one of the many fleeting tattooers throughout history, who opted in only for the duration of the customary war-time business boom. As a seaport city and home to a U.S. Naval yard, Boston turned out a healthy supply of sailors hankering to be inked. With the advent of the Spanish American War, and hundreds more patriotic seamen added to the customer pool, Boston’s tattoo business would have been in full force at the turn of the century.

Dime museum tattoo artist/tattooed attraction, Captain Fred McKay, and Hanover Street tattooer, Otto Mason, were two well-known Boston practitioners catering to the ranks. Both are named in Boston City Directories and/or amusement ads. (Tattoo artists Ed Smith and Frank Howard (real name Franklin Howard Packard) came soon after). Fellowes, however, never advertised as a tattoo artist, suggesting he may have been in business just a short time and/or in a limited capacity. According to directories, Bigelow and Dowse provided his primary employment from 1897 until his death in 1923. Just the same, I’m optimistic further digging will uncover something more about his career.

Update 2019: I’ve found more information regarding my C.H. Fellowes’ sketchbook discovery. As it turns out, William C. Sturtevant had little to do with researching the identity of Fellowes. This will be expanded on at a later date.

Read more about my Fellowes’ discovery in this 2014 Boston Globe Write-up: A mysterious 19th-century tattoo artist, identified at last.

“As Sturtevant concluded in writing on Fellowes, he and other artists like him were working in a popular folk art style that has turned out to be of lasting significance. The Mystic Seaport museum has said it is planning to update its description of the materials in light of Nyssen’s research. The story of tattoos may be less ephemeral than we thought: Much like tattoos themselves, history fades over time, but with a little upkeep it can leave some permanent marks of its own.” -Luke O’Neil, Boston Globe

See my Find-A-Grave memorials, here, for my Fellowes’ family/genealogical research.

For further context on C.H. Fellowes and my discovery see: Tattoo! At the American Museum of Folk Art by Jamie Jelinski, Sang Bleu Magazine (2014), as well as, the Tattoo Archive Page: C.H. Fellowes

My history/discovery of C.H. Fellowes was originally published on Carmen Nyssen’s Tumblr “Tattoo Tidbits” February of 2014. Updated on www.buzzworthytattoo.com May 28, 2015 @19:05:33