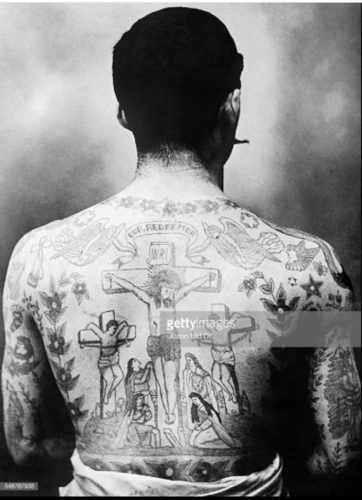

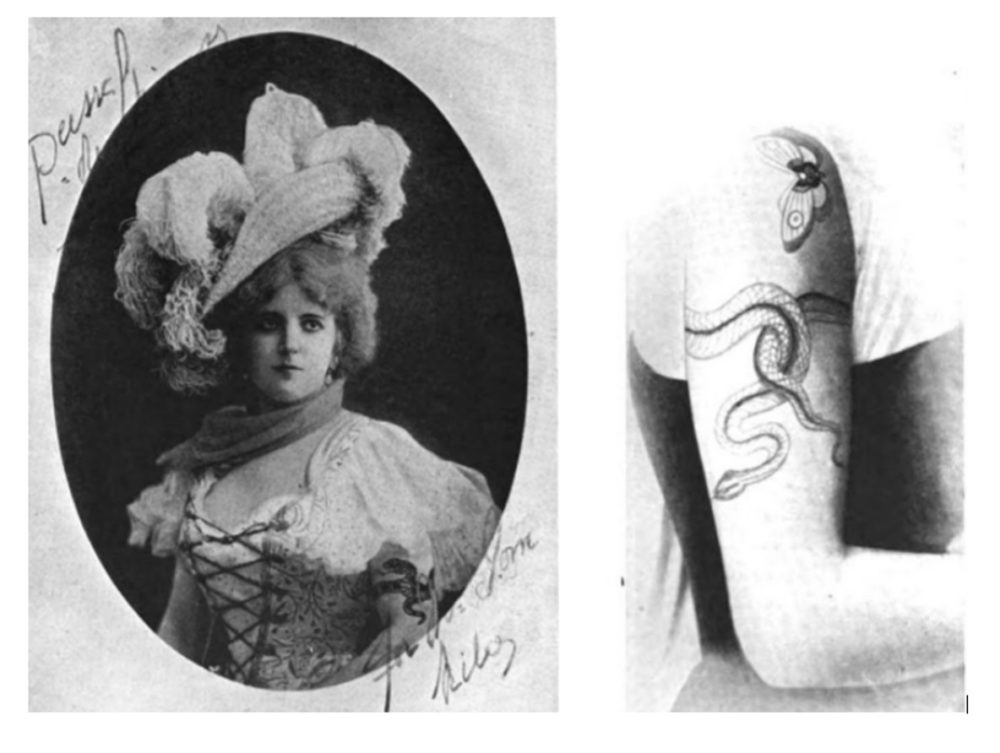

Tattooed man/tattoo artist Jim Wilson. Getty Images. “Tattoos, tattooed man, by tattoo artist Tom Riley-date unknown, around 1903.”

Tom Riley: The Making of a Tattooist

Researched & Written by Carmen Nyssen

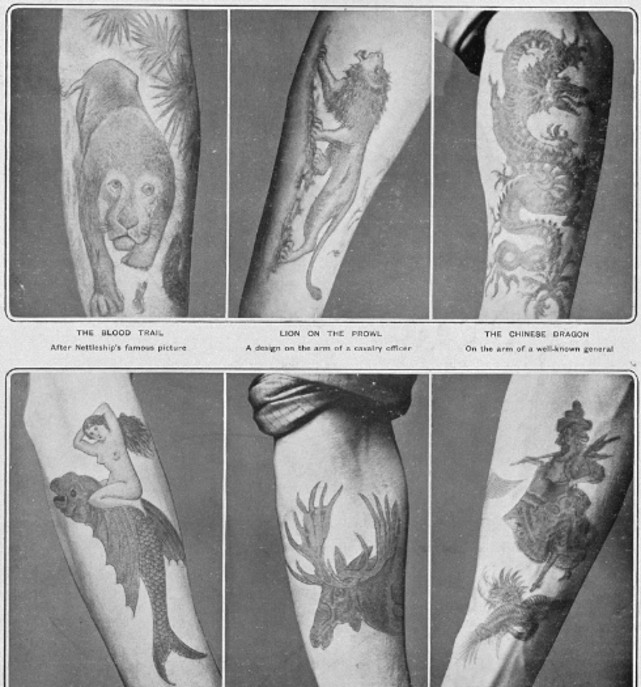

Outwardly, the making of Tom Riley’s career as a tattooist parallels that of other notable British practitioners of his era. What is commonly told is that he learned to tattoo while serving in the military, earned his illustrious reputation engraving designs on royalty and high society, and helped transform tattooing in the U.K. from a “sailor’s art” into a high art form. Just like his most excellent contemporaries, Riley’s beautifully executed tattoo work—delicate, fine-lined, and heavily influenced by the designs of Japanese masters—helped lay the foundation of what is known today as the “English style” of tattooing.

Lurking behind the similarities, however, is Riley’s unique story—all the guts and glory of his tattoo career that more deeply informs the greater historical picture. Although a complete chronicle of his path to becoming one of the most prominent tattooists of his generation is out of reach, a preliminary investigation in genealogical and archival records has at least revealed some of the richness of his life course.

Tom Riley’s Pre-Tattooing Days

Given that Tom Riley’s service in the Second Boer War (1899-1902) is well-noted in tattoo history, it’s fitting that his military record held the clues to uncovering details of his early life. Military documents state that on February 9, 1900, 28-year-old “Thomas Riley,” tattoo artist born in Armley, near Leeds, volunteered to serve with the Imperial Yeomanry in South Africa. Fortuitously, his file also lists his next-of-kin, sister “Sarah Jane Riley” of “9 Main” in Armley. This latter bit, after cross-referencing of further records, is what led to a key discovery. It turns out, Sarah Jane was married to a man named Jim Riley, but was the daughter of John Scott Clarkson and his wife Margaret. And “Tom Riley” was the son of the same couple, born Thomas Clarkson, in 1870.

Additional digging uncovered that Thomas Clarkson, aka Tom Riley, did not set out to be a tattoo artist; he was humbly destined for a working-class career like his father, a bricklayer and railway porter. At age 17, he was apprenticed as a brickmaker at William Ingham & Sons, in nearby Wortley. Though quite young, he must have realized that an ordinary trade wasn’t his suit, as this is when he first joined the military and found his true calling.

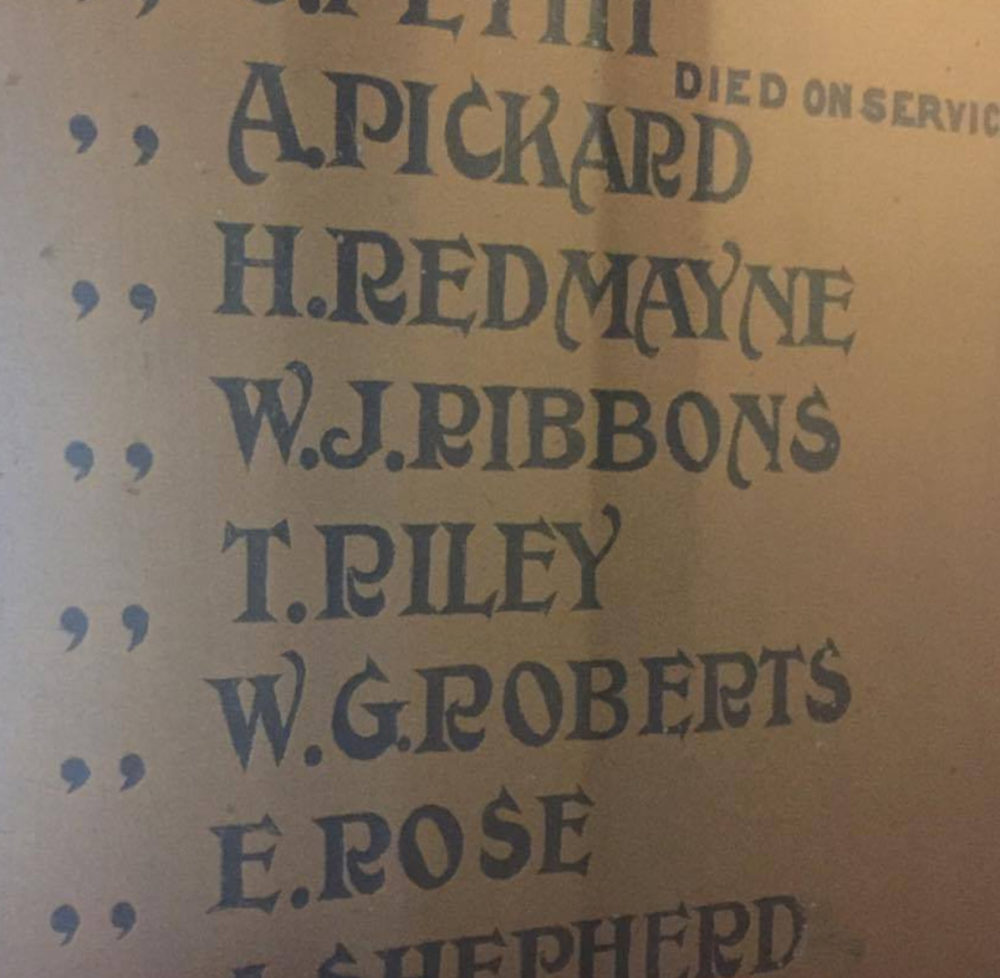

Though born a Clarkson, Tom Riley the tattooist is immortalized

on the Leeds Town Hall ‘Wall of Imperial Yeomanry Volunteers’ under his alias.

Tom Riley, Leeds Town Hall wall. Photo by Rich Hardy

Tom Riley’s Military Tattooing

According to two earlier military records (under the name Thomas Clarkson), in March of 1889, Riley enlisted with the West York Regiment, and in September, with the Argyle Sutherland Highlanders. Riley had encountered tattooing beforehand (an anchor adorned his left forearm), but as he informed interviewer Mulvaney Ouseley in 1900, he learned the art while in the military, sacrificing all free hours tattooing officers and servicemen in the barracks. Interestingly, his last station, in February of 1890, was in the military-based town of Aldershot, where tattooist Sutherland MacDonald (1860-1942) had been set up at the 9 Gordon Road Turkish Baths as recently as 1889.

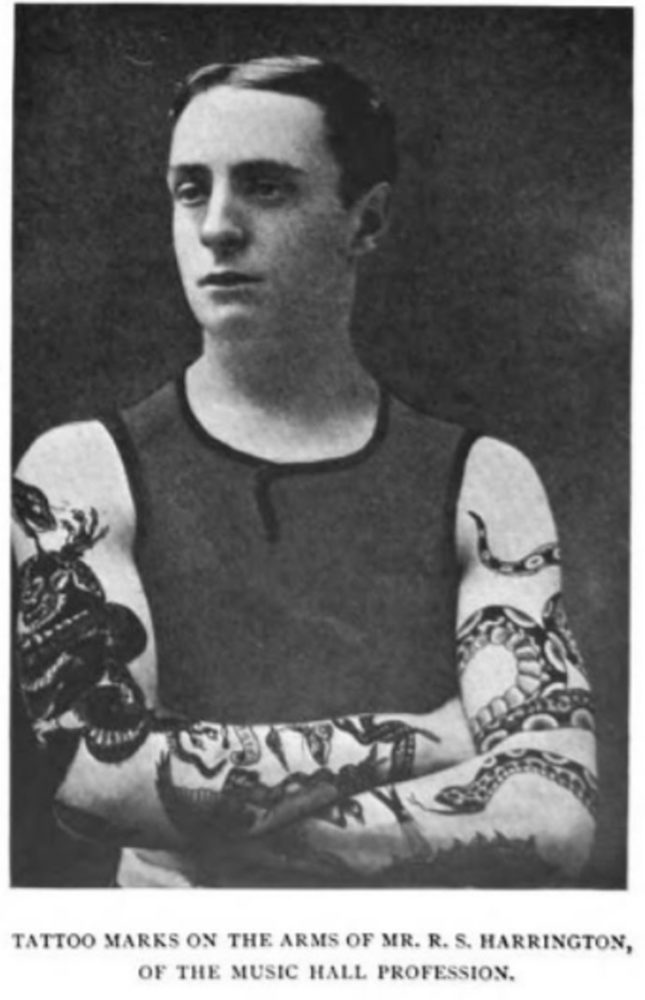

R.S. Harrington tattooed by Tom Riley. The English Illustrated. April to Sept. 1903.

As Riley further outlined for Ouseley, after his discharge from the military, he took drawing lessons in Leeds near his family’s residence, then “opened up in Liverpool and afterwards Glasgow.” At this point, unfortunately, neither his military tattooing, nor his whereabouts in the immediate years afterward, can be substantiated outside oral history. Yet, there’s little doubt he was working as a tattoo artist and progressing his skills throughout this period.

Burgeoning Tattooist Tom Riley

By 1895, only several years later, Tom Riley had become a full-fledged practitioner of tattooing—curiously having adopted his brother-in-law’s surname (End note 1). April of 1895 newspaper notices place “Professor Riley,” “tattooist” at Oswald Stoll’s Cardiff (Wales) Panopticon Theatre, “efficiently” tattooing a person on stage. Another ad, dated July of 1895, pins him down at 47 Salthouse Lane, near the river docks in Hull, across from the Sailor’s home. According to city directories, this location was the “Dry Goods & Sundries” shop of James Archer.

Apparently, in these early days of obscurity, Riley accepted work wherever he could find it, quietly honing his craft and paying his dues. One of his ads, in October of 1895, solicited crests and monograms, and even more mundane designs like initials—in fact “anything”—which he avowed would be “neatly carefully” executed. This time spent so conscientiously practicing and studying primed Riley for the next level of his career.

Tattoo by Sutherland MacDonald. Pearson’s. 1902.

The budding artist was no doubt inspired by Sutherland MacDonald, an exceptionally talented tattooist ten-years his senior, who had already made quite a name. In 1894, MacDonald obtained the first British electric tattoo machine patent (End note 2). By the early 1890s, he had also garnered a following etching the skin of royalty with designs fashioned after the exquisite artwork of Japanese tattoo artists—meticulously and expertly pricked into the skin with hand tools. Like his elder contemporary, Riley strived to master the West’s appropriated version of Japanese tattooing, using both electric machines and traditional hand tools in executing his tattoos (End note 2).

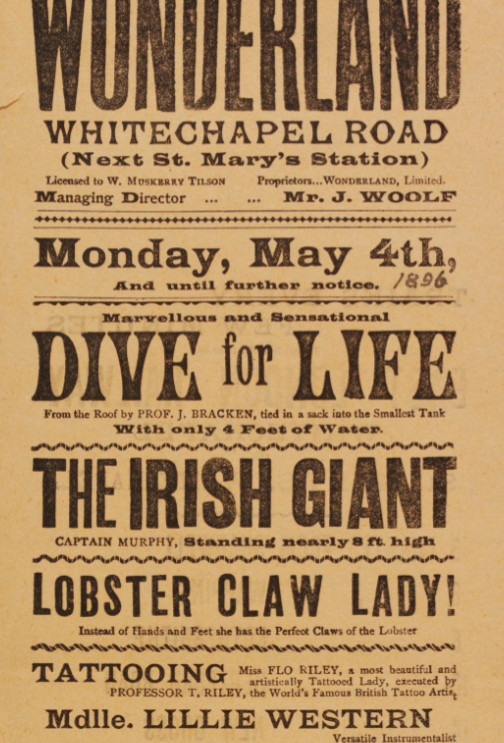

By the spring of 1896, Riley was ready to showcase his own talents on a grand scale: he had transformed a woman, “Flo Riley” (Endnote 3), into a “…gallery of Japanese art.” She exhibited as a living testimony of his talents, while he tattooed alongside her on the amusement show circuit. Their first engagement in March—as Miss Flo Riley, tattooed marvel, and Professor Tom Riley, first-class English tattoo artist—was a six-week run at the Manchester Hotel in Birmingham. The next gig, in May, was at J. Woolf’s Wonderland show hall, 236 White Chapel in London. After months of hustle building a reputation via these appearances, the duo finally landed a coveted spot at one of London’s most popular amusement establishments.

Royal Aquarium Tattooist(s)

Royal Aquarium Tattooist(s)

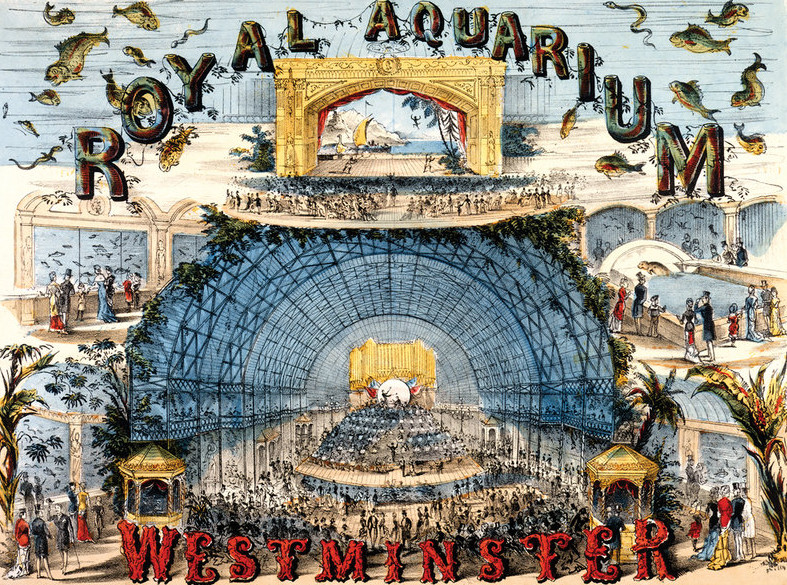

By October of 1896, Tom and Flo Riley had settled at the well-patronized Royal Aquarium (End note 4), where they fared well among a diversity of showfolk and oddity performers. At first, notices for this engagement boasted “Professor T. Riley,” tattooing “crests, monograms, initials and Japanese and Burmese art,” “neatly and carefully” in four colors. But subsequent billings, naming an assistant, indicate he soon required help attending the flow of clientele. And not just from anyone. Royal Aquarium managers were surely pleased to announce, in December and following months, that “Professor Riley” and the extraordinarily novel—perhaps first, one and only—female tattooist, “Mdlle. Riley,” were “prepared to tattoo visitors all day” in the promenade court. A year later, Riley and his unusual partner were still busy tattooing at the Royal Aquarium.

Courtesy British Library prints.

Securing such a long engagement at the famed amusement hall in itself had boosted Riley’s tattooing career, but it additionally exposed his talents to a wider customer base. From this platform, word of his ability spread throughout the great metropolis of London, up to the ranks of royalty and high society. Upon first realizing he was on pace with the top echelon of his craft, Riley modestly assured potential customers of his credentials in advertisements.

In an October 23, 1897 To-Day ad, Riley touted his “bright permanent yellow” tattoo ink contribution, but merely alluded to his antiseptic operation, and encouraged would-be clientele to compare the work of a few tattoo artists before committing to any one. Mindful, too, not to exploit the tattooing of distinguished personages, he promised anonymity to those who chose his services. While Riley treaded lightly in his new arena, however, he quickly found himself at odds with competition.

Rivaling Alfred South

In 1897, a royalty-inspired tattoo fashion craze among socialites upped competition between London tattoo artists. The full-blown war started in May of 1898, when Riley was asked to vacate his stall at the Royal Aquarium (allegedly because he was tending to his suicidal wife), and Austrian born Alfred South (1872-1934, real name Alfred Charles George Schmidt)—tattoo artist of 18 months—took it over. Appalled at being replaced by an “amateur” piggybacking on his reputation, Riley persistently harassed South, demanding he relinquish the spot. But to no avail. The ordeal ended in court, in July, with South claiming he was just as much a professional as Riley and the judge warning Riley to keep the peace and move on.

—

Tatler, 25 Nov. 1903. Wellcome Library, London

—

Despite the upheaval, the resilient and talented Riley (and Flo) had already secured another prime position at the Earl’s Court Exhibition Centre in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea—working briefly with Japanese tattoo master Horitoyo no less. In this posh, new locale, Riley continued building a rapport with high society patrons, and as with the renowned Sutherland MacDonald, he started attracting his share of publicity in newspapers and magazines.

The Wheel, ca 1900 (Earls Court London). Photographer: James Valentine. Courtesy of http://servatius.blogspot.com/2013/10/

—

Rivaling Sutherland MacDonald

Not surprisingly, Riley’s burgeoning success provoked further problems with competitors. An article published in the December 15, 1898 Harmsworth Christmas Magazine—heralding his work as not only the best in London, but in the world, and stating that he had tattooed more distinguished people than any other tattoo artist—was the next major fodder for contention.

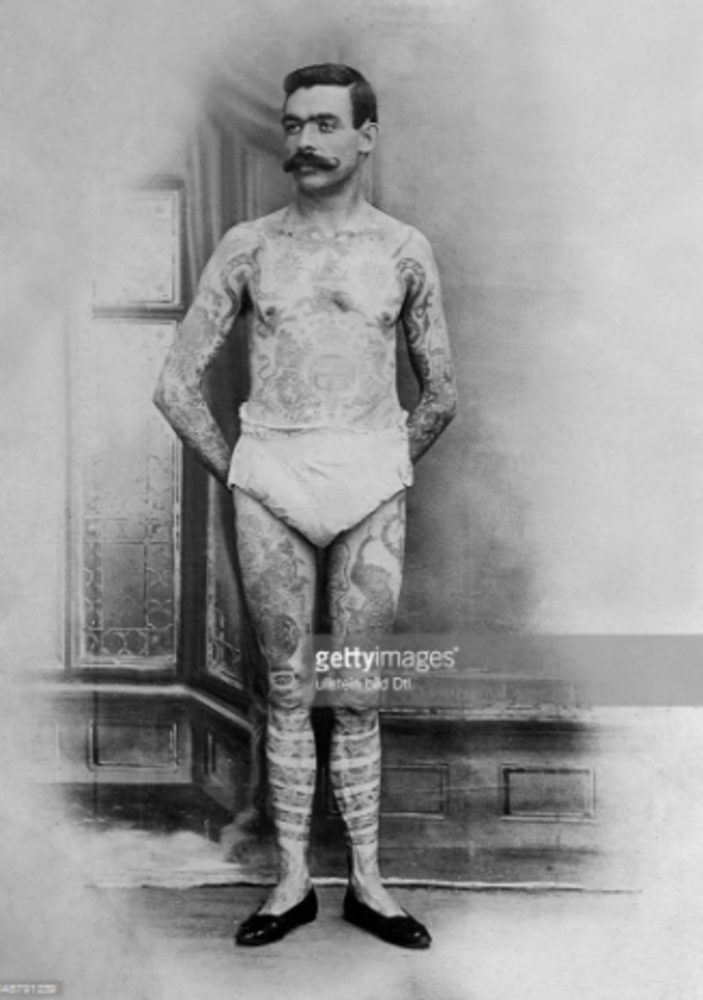

Sutherland MacDonald. Pearson’s. 1902.

Entitled ‘Tattoo Royalty,’ the article mentioned several royal persons Sutherland MacDonald had tattooed, including the Duke of York and Prince George along with “facsimiles” of their tattoos, but it failed to name MacDonald at all. Whether the omission was accidental or deliberate—on the part of Riley or the author—MacDonald was miffed at the article’s impression that Riley had tattooed royalty actually tattooed by him. Probably likewise annoyed at the gushing accolades given Riley, he countered the article with his best undermining retort.

On January 4, 1899, he placed a notice in the London Standard, cheekily stating that he was the only English “tattooist”—a term he used to differentiate his artful work from that of common trade tattoo artists—with knowledge and “Royal authority” to confirm that the so-called facsimiles of his clients’ tattoos were “false” (not exact replicas). In so many words, he had accused Riley of being a less-talented fraud. Considering that numerous publications quoted the article anyway—complimenting Riley—his comeback was mostly a null effort.

Battling Society Tattooists

The bad blood instigated by such incidents set the stage for years of posturing among the three tattoo artists, who despite their staggered experience, all came to be represented as equals in the media—celebrated as “Society Tattooists.”

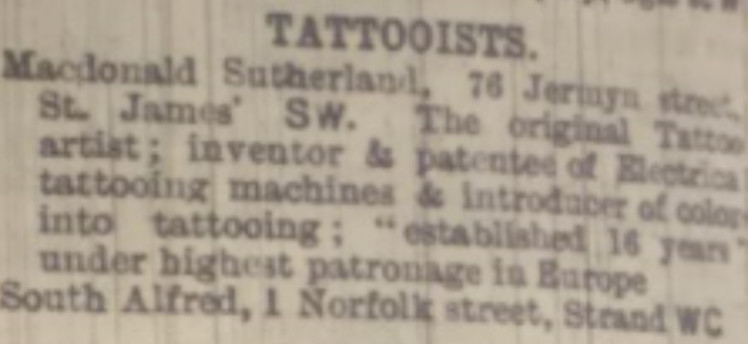

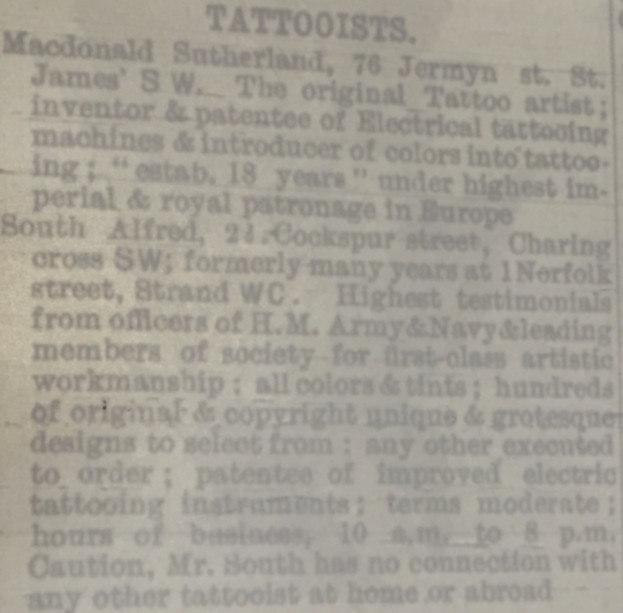

In asserting his expertise, in 1899, MacDonald listed a virtual resume in the London Post Office Directory, itemizing all his accomplishments, including his tattoo machine patent, inks he had introduced to the trade, and his claim as “the original tattooist.” He additionally took to advertising as the “Leading Tattooist in Europe” after an engagement in Russia.

Tattooists Listing, 1899 London Post Office Directory

—

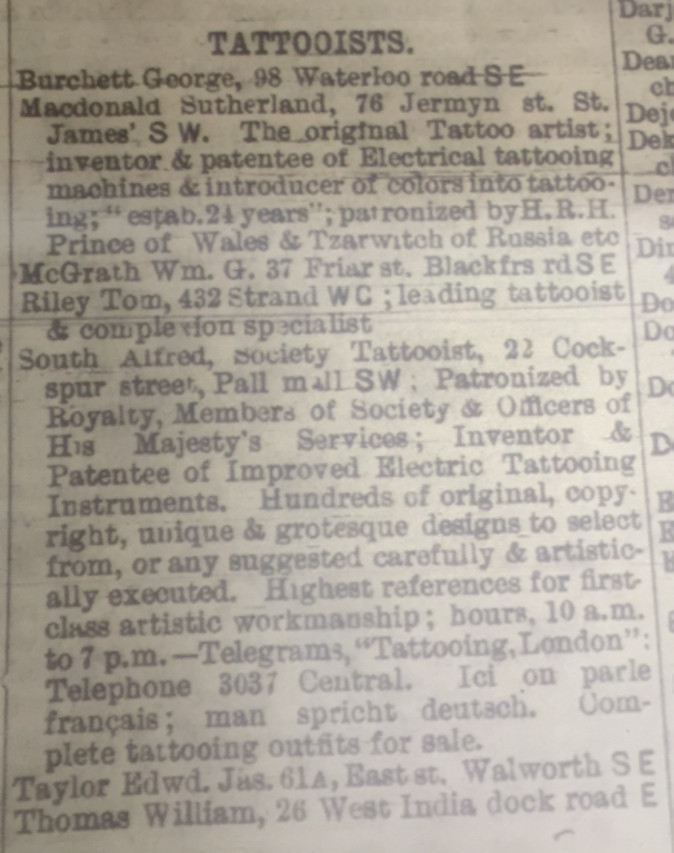

Alfred South—a newcomer who somehow escaped conviction when a man he tattooed died of blood poisoning in April of 1899—followed suit with a lengthy spiel in 1900, after patenting the second British electric tattoo machine that year (based on a doorbell). Both South’s ads and directory listings went so far as to uphold himself over competitors by nitpicking their business endeavors: if they had assistants he stressed that he had no assistants; if they worked overseas he pointed out that he was not associated with anyone abroad; if they offered cosmetic tattooing of lips and cheeks he clarified that he did not offer it (though he later did), and so forth.

Tattooists Listing, 1900 London Post Office Directory

—

Riley, perhaps wanting to rely more on his good name, chose a subtler approach than his cohorts. Although the “leading society tattooist” had started namedropping notable customers in interviews, and in 1903 made the dubious claim he helped his American “cousin” Samuel F. O’Reilly with his 1891 electric tattoo machine patent (End notes 2, 5), he wasn’t nearly as caught up in the self-aggrandizing. His ads were to the point and he forewent a directory listing altogether until 1904, when he moved to 432 Strand. Even then, he left it simple: “leading tattooist & complexion specialist.”

Tattooists Listing, 1904 London Post Office Directory

—

Tom Riley World Traveling Tattooist

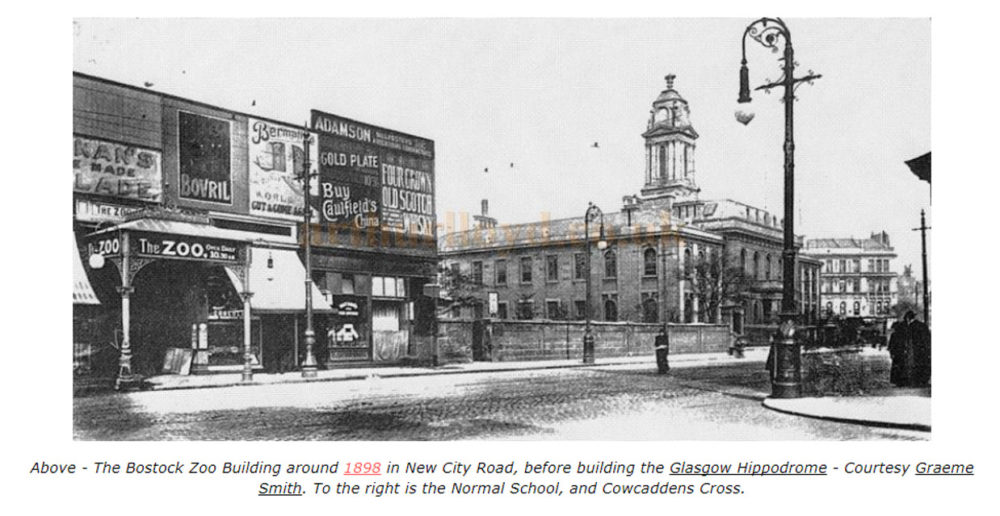

Riley, it seems, was not so concerned with vying for celebrity in London as he was on expanding his portfolio and sharing his work the world over. London remained his headquarters for some years more—at the the Royal Aquarium 1900-1901, Earl’s court 1901-1903, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Olympia 1903, 432 Strand 1903-1906, and The Façade in 1905. But, while Flo exhibited his beautiful artistry around the U.K. at various venues, he increasingly demonstrated his talents across the globe. In February of 1899, he and Flo secured a short engagement at E. H. Bostock’s Glasgow Zoo building in Scotland, where he guaranteed electric tattooing in “nine or more colors without pain.”

Courtesy of ArthurLloyd.co.uk. The Scottish Zoo and Variety Circus, and Glasgow Hippodrome, New City Road, Glasgow

—

Then, in coming months, Riley, at least, traveled as far as Cairo, having been commissioned by the infamous heiress Princess Chimay (Clara Ward) to tattoo her arms as well as tint her lips and cheeks—the latest fashion vogue. During his stay, he supposedly also worked on members of Lord Kitchener’s staff, South African millionaire Mr. Beit, and the Turkish Minister.

Princess Chimay (Clara Ward) tattooed by Tom Riley. The English Illustrated. April to Sept. 1903.

—

When tattooing experienced another business explosion at the onset of the Second Boer War, starting in October, Riley didn’t stay put in London to compete for customers. The following February, he shrewdly volunteered for the Leeds Imperial Yeomanry and made quite a bank roll—from March to October 1900—tattooing high-ranking officers on the South African battlefield as part of Col. Younghusband’s Maxim Gun Contingent.

Tom Riley tattooing on the South African battlefield. The English Illustrated. April to Sept. 1903.

—

Sutherland MacDonald and Alfred South occasionally tattooed in foreign lands at the behest of eminent persons. But it was Riley who had carved a genuine niche as the “World’s Famous Tattooist” at the close of the century. And he continued doing so. In October of 1901, he made an appearance across the Atlantic Ocean at Huber’s Dime Museum in New York City, billed as the “famous London Society tattooist.” In 1904, Princess Chimay called for him again in Paris to cover up an ex-lover’s portrait he had previously tattooed on her arm. 1909 found him in Paris as well.

Tom Riley’s Tattoo Legacy

The world-famous Tom Riley—from his humble beginnings as a working-class boy in Leeds to his days starting out as the “best traveling tattoo artist”—rose to the top of his craft through practice and perseverance. Unlike his competitors, he wasn’t the originator of his refined style of tattooing, and he didn’t patent an electric tattoo machine, but he was still a visionary who saw the possibilities of the art form and determinedly pushed the tattoo trade to new levels with his artistry and entrepreneurship. Although he never operated from his own tattoo shop, it’s possible he wouldn’t have influenced tattooing quite the same way confined to one place. In a time when there were few high-quality tattoo artists, his travels enabled a true art form to shine grandly and spread to further reaches.

For Posterity:

Examples of tattoo work from those Riley mentored is scarce, but for posterity’s sake, they should be named. Besides Flo Riley, he taught Lincolnshire tattoo artist Jim Wilson, his representative in 1903 at the Glasgow Zoo, and purportedly, Liverpool tattoo artist Bill Donnelly. Both of them worked on Sands Street in Brooklyn, New York in the 1920s, and did some additional globetrotting of their own. (Click link for Jim Wilson article)

End Notes:

1-All records indicate that Tom Riley’s brother-in-law, Jim Riley, was a bricklayer in Leeds. Jim doesn’t appear to have been a tattoo artist, so it’s not clear why Riley used his name. One possibility is that Riley’s family forbade him to work under the Clarkson name. Since Jim Riley’s parents had died by 1895, he might have allowed the use of their surname.

On a related note, George Burchett’s Memoirs of a Tattooist states that Tom Riley had a younger brother who assisted him with tattooing. However, Riley only had two sisters, Sarah Jane and Annie, and no brothers. The information likely stems from a misinterpretation of an earlier publication. As pointed out by Jon Reiter in his more recent biography about George Burchett, the book is filled with such inaccuracies.

The misinformation about Tom Riley’s brother tattoo artist seems to stem from an 1897 Strand Magazine article, which mentions the American “Brothers Riley,” but not Tom Riley. This might be a reference to New York Bowery tattoo artist, Sam O’Reilly. Although definitive proof that his brothers worked as tattoo artists alongside him has yet to surface, it’s not out of the question. O’Reilly’s younger brother John O’Reilly, at the very least, worked as a dime museum tattooed attraction. A second clue lies within an antique tattoo design book page attributed to O’Reilly with the initials “M. F. O’R” scrolled underneath a design. Interestingly, O’Reilly had a brother, Maurice F. O’Reilly, who died in 1900; his death certificate lists his address as 5 Chatham Square, the same as O’Reilly’s tattoo shop.

To further note: An August 20, 1897 St. Louis-Dispatch article does mention two tattooers working from a hole in-the-wall in Chatham Square, but it might refer to O’Reilly and his partner Elmer Getchell, who had joined him at his 5 Chatham Square tattoo shop sometime after March of 1897 and before October. An 1898 pitch pamphlet for British tattooed man ‘Ted Frisco’ also mentions the American Riley brothers and states that Ted had been tattooed in a Dime Museum on the New York Bowery. However, given the hokey nature of pitch items, the blurb about the Rileys could have been borrowed from the 1897 Strand Magazine article and the rest of the story fabricated as a stage spiel.

2-Tattoo artists were using electric tattoo machines as early as 1889 in the U.S., and probably near the same time in the U.K. Although tattoo lore states that Tom Riley patented an electric tattoo machine in 1891, there’s no evidence to support the claim. For a full explanation of early tattoo machine history, including clarification on Riley’s alleged patent, see Buzzworthy Tattoo History article Early Tinkerers of Electric Tattooing.

3-It’s likely that Flo Riley was Tom Riley’s wife, as she was associated with him for many years, but it has been difficult to confirm the relationship. His wife’s name in the 1901 census is listed as “Dolly.” Due to Riley’s two names, and the lack of information about Flo and Dolly’s identities, locating evidence has been quite a task.

4-Several writings state that Riley first worked at the Royal Aquarium in 1893 rather than 1896, the year New Era amusement announcements first place the Rileys at the Royal Aquarium. The confusion might be due to a Google Books link labeled “Today (London, England : 1893), Volumes 16-17. By Jerome Klapka Jerome, Barry Pain.” The link actually leads to compilation book of 1897, not 1893, To-Day issues, which includes Riley’s 1897 ads for the Royal Aquarium. 1893 is the year To-Day was founded by Jerome Klapka.

5-Tom Riley’s claim that he was a “cousin” of Sam O’Reilly would be difficult to confirm or rule out without compiling a comprehensive genealogical tree. Although a 1900 article entitled ‘Marked for Life’ infers that Riley was an Irishman and spoke with an Irish accent, both Riley and his parents were born and raised near Leeds, England. Samuel O’Reilly’s parents immigrated from Ireland to the U.S. sometime before 1854, when O’Reilly was born in Connecticut.

Published October 14, 2017